| Invention Name | Elevator (Greek Water-Powered Lifts) |

| Short Definition | Vertical lifting systems that move loads using ropes, pulleys, and drums, sometimes supported by water-driven rotary power or water-pressure devices. |

| Approx. Date / Era | Classical–Hellenistic to early Roman-era descriptions (roughly 5th c. BCE–1st c. CE) Approximate |

| Date Certainty | Approximate (survives mainly through later texts and reconstructions) |

| Geography | Eastern Mediterranean; Greek world; Hellenistic centers such as Alexandria |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Anon. / collective engineering tradition; associated names include Archimedes, Ctesibius, and Heron (Hero) Contested |

| Category | Mechanical Engineering; Hydraulics; Construction & Waterworks |

| Importance |

|

| Need / Driver | Hilltop cities; wells and cisterns; large building projects; steady lifting with limited muscle power |

| How It Works (Simple) | Rotary motion turns a drum (windlass) to wind rope; pulleys can multiply force; water devices can supply motion or pressure |

| Materials / Tech Base | Timber frames; hemp/flax ropes; bronze/iron fittings; wooden sheaves; water flow and valves (for pumps) |

| Early Use Contexts | Construction yards; ports; workshops; wells; public water management |

| Spread Path | Greek practice → Greco-Roman technical writing → later Mediterranean engineering traditions |

| Derived Developments | Advanced cranes; geared hoists; hydraulic lifting concepts; modern elevators (traction & hydraulic) |

| Impact Areas | Architecture; Urban Water; Craft & Industry; Infrastructure; Education (mechanics) |

| Debates / Views | “First elevator” claims tied to famous individuals are Contested; surviving texts often reflect later compilation and transmission |

| Precursors → Successors | Ramps & hand-hoists → compound pulleys & windlasses → hydraulic lifts → electric traction elevators |

| Related Variations | Windlass hoists; compound pulley blocks; bucket-chain water lifters; drum (“tympanum”) water wheels; force pumps |

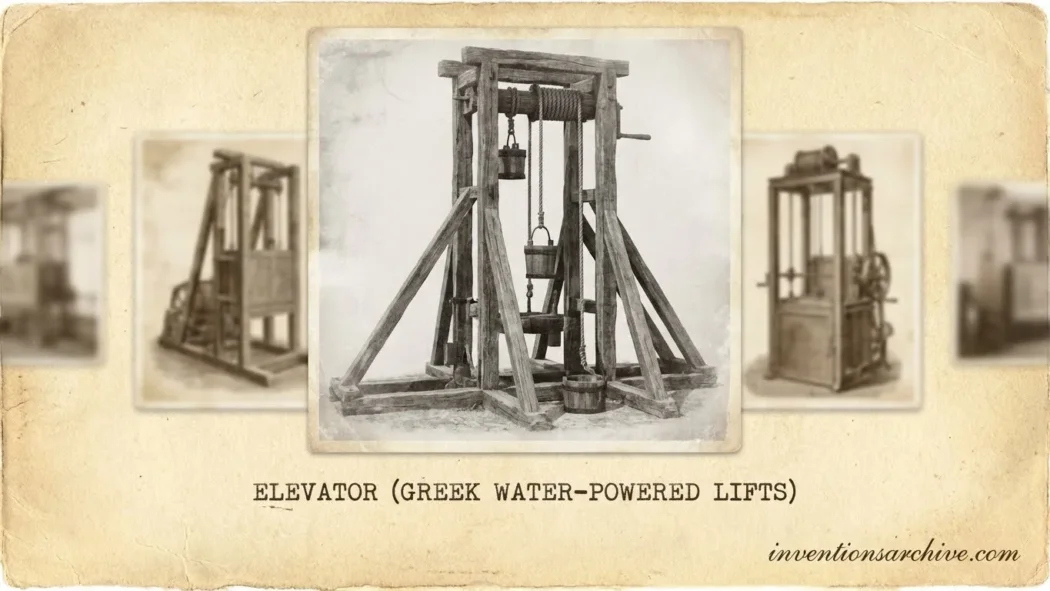

Elevators feel like a modern promise: up becomes easy. Yet the underlying idea is ancient. Greek engineers treated vertical movement as a problem of motion, force, and control. Their world produced hoists for stone and timber, and water-powered devices that could lift water itself. Put together, these traditions form a clear ancestor to the elevator story—grounded in simple machines, refined by practical needs, and carried forward through technical writing.

Table of Contents

What It Is

In ancient contexts, the “elevator” idea is best understood as a vertical lifting system rather than a passenger cabin. The core is a platform or load moved along a vertical path by rope, pulleys, and a drum (windlass). Water enters the story in two ways: it can be the thing being lifted, and it can also be a source of power when flowing water turns a wheel or supports pressure-based pumping.

- Hoist-style lifts: rope wound on a drum; used for stone, timber, cargo, and tools.

- Pulley lifts: multiple sheaves reduce the effort needed; ideal for heavier loads.

- Water-lifting machines: devices that raise water from wells or channels—often the clearest ancient example of “lift powered by nature.”

Why Water Power Mattered

Greek cities often sat on high ground. That meant water was not always nearby. Lifting water up to homes, workshops, and public spaces demanded steady energy, day after day. Ancient writers note that this pressure encouraged water lifting solutions and careful management across long periods.Details

A Simple Connection

Flowing water is a reliable mover. If it can turn a wheel, it can turn a windlass. That rotary motion can then wind rope around a drum and raise a load. Even when direct “waterwheel hoists” are hard to prove for every site, the mechanical pathway is clear and fits the broader Greek tradition of converting one kind of motion into another.

- Water flow → wheel rotation

- Rotation → drum turns (windlass)

- Drum → rope winds

- Rope and pulleys → load rises

Early Evidence and Timeline

Ancient engineering rarely arrives as a single “launch date.” Instead, it appears as a chain: practical devices, then written descriptions, then later copying and commentary. A famous Roman-era technical description explains how a capstan turns a drum and axle so ropes tighten and lift loads smoothly—an explicit blueprint for the rope-and-drum logic behind elevators.Details

| Period | What We Can Say Safely | Lift Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Bronze Age–Classical Approx. | Wells, cisterns, and early lifting methods spread across the Aegean world. | Established daily need for vertical movement of water and materials. |

| Hellenistic Era Approx. | Rapid growth of technical writing and mechanical experimentation in major centers. | Strong foundations for pulleys, drums, and water machinery. |

| 1st c. BCE Firm | Detailed descriptions of cranes and compound pulley systems circulate in technical literature. | Clear documentation for controlled lifting using drums and blocks. |

| 1st c. CE Approx. | Greek mechanics is compiled, taught, and transmitted across languages and centuries. | Concepts of mechanical advantage and device design become easier to copy and adapt. |

How It Works

Turning Motion

The lift begins with rotation: a capstan, crank, or wheel. In a water-powered setting, that rotation can come from a waterwheel or a stream-driven mechanism. The goal is steady torque, not speed.

- Capstan / windlass (human or animal power)

- Water-driven wheel (natural flow → rotation)

- Geared trains (optional; for more force with slower turning)

Lifting Motion

Rotation turns a drum. Rope winds onto it. As the rope shortens, the load rises. Add pulleys, and the same input can lift heavier loads with less force. This is the heart of mechanical advantage.

- Drum winds rope in a controlled way

- Pulleys share the load across rope segments

- Frame and guides keep motion stable and predictable

Where “Hydraulic” Fits In

Greek and Greco-Roman water technology also includes pressure. A classic example is the force pump tradition linked to Ctesibius: paired cylinders, valves, and pistons that move water upward with controlled strokes.Details That is not a cabin elevator, yet it shows the same idea: fluid power used to defeat gravity in a repeatable way.

Lift Types and Variations

“Greek water-powered lifts” is best read as a family of devices. Some lift water, some lift loads, and some combine ideas that later converge into modern elevator designs.

Drum-and-Capstan Hoists

A drum on an axle winds rope as a capstan turns. This produces smooth raising and lowering when the system is well balanced. It is the closest ancient match to the “winch elevator” concept, with rope management at its center.

Compound Pulley Blocks

With multiple sheaves, a pulley system increases mechanical advantage. The tradeoff is longer rope travel. For builders, that trade was often worth it, especially when precision mattered more than speed.

Waterwheel-Assisted Windlasses

A waterwheel delivers continuous rotation. Pair that with a windlass, and the machine can lift steadily without constant muscle input. Even where the historical record is fragmentary, the engineering logic is straightforward: water turns the wheel, the wheel turns the drum, the drum winds the rope.

Tympanum Drums and Compartment Wheels

Some ancient water-lifting designs use a rotating drum or wheel with compartments that scoop and carry water upward. The motion is “elevator-like” in a literal sense: water rises in steps as the wheel turns. These devices sit at the meeting point of geometry and craft, with careful sealing and balanced rotation.

Archimedean Screw Lifts

The screw lift moves water through a rotating helical channel. It converts rotation into steady upward flow, a clean demonstration of how rotation can produce rise. In elevator history, its importance is conceptual: it shows repeatable lifting driven by simple motion.

Chain-of-Pots and Bucket Chains

Bucket chains lift water in a moving loop. Each container is small, yet the system can deliver a steady stream. The “lift” here is distributed: many small upward moves happen in sequence, like a conveyor rising through space.

Force Pumps and Valve Systems

Piston pumps linked to Greek hydraulic knowledge rely on valves and pressure. This is an early ancestor to the later idea of using pressurized fluid to raise a load. The key insight is not the exact shape of a machine; it is the controlled use of one-way flow.

Where These Lifts Appeared

Greek lifting systems make the most sense when placed in daily settings. They served practical needs and supported the rhythm of civic life. Think materials, water, and repeated tasks.

| Setting | What Was Lifted | Why It Helped |

|---|---|---|

| Wells and cisterns | Water | Supported hilltop living with limited local supply |

| Construction yards | Stone blocks, column drums, timber | Reduced strain; improved placement and alignment |

| Ports and warehouses | Crates, amphorae, tools | Moved goods between quay and storage levels |

| Workshops | Materials and finished items | Kept vertical space usable in compact buildings |

Legacy and Ideas

The Greek contribution is not a single patented machine. It is a toolkit: pulleys, drums, screws, pumps, and an analytical habit of thinking in ratios and forces. Later centuries built on that toolkit, sometimes through direct copying, sometimes through reinvention.

A Note on Transmission

Some major Greek mechanical texts survive through complex paths. For example, Heron’s Mechanica is often described as surviving in full only through an Arabic translation, with the tradition shaped by copying and reinterpretation over time.Details That matters when dating devices: the ideas are real, yet the paperwork can be late.

FAQ

Did ancient Greeks build passenger elevators?

The strongest evidence points to load lifting: hoists for building materials, workshop goods, and water. That said, the mechanical logic—rope, drum, pulleys, controlled movement—matches the core of later elevators.

What makes a lift “water-powered” in this context?

Two ideas matter. First, water can provide rotary motion by turning a wheel. Second, water technology can use pressure and valves to move fluid upward. Both sit close to the elevator problem: lifting against gravity in a steady, repeatable way.

What is the key mechanism behind early hoist-style elevators?

A drum (windlass) winds rope. Pulleys can multiply force. Together they turn rotation into upward travel, with controlled motion that can be paused and resumed.

How do water-lifting machines connect to elevator history?

They prove that ancient engineers could design systems for repeated lifting using natural power sources and careful control. The “load” is water, but the engineering principles—energy input, transmission, stability—carry over.

Why do dates and “first inventor” claims vary so much?

Many devices were part of collective practice. Written records can be later than the invention itself, and some texts traveled through translation and editing. That combination makes exact firsts hard to lock down with certainty.