| Invention Name | Paper |

| Short Definition | Thin sheet of plant fibers bonded into a flat surface for writing, printing, and wrapping. |

| Approx. Date / Period | 2nd century BCE (Approx.) to early centuries CE (Approx.); 105 CE (Recorded attribution); “First paper” (Debated) |

| Geography | China (Han period) |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Han China; Cai Lun (attributed); anonymous earlier makers |

| Category | Material; Information; Packaging |

| Importance |

|

| Need / Driver | Lightweight writing surface; less costly than silk; easier than heavy bamboo |

| How It Works | Cellulose fibers interlock as water drains; drying forms a stable sheet |

| Material / Technology Basis | Cellulose; fiber slurry; screen forming; sizing (reduced absorbency) |

| Earliest Uses | Wrapping; medicine packaging; letters and records |

| Spread Route | East Asia → Central Asia → West Asia → Europe |

| Derived Developments | Books; mass printing; standardized forms; packaging systems |

| Impact Areas | Education, Administration, Commerce, Art |

| Debates / Different Views | Earliest evidence (varies by find); Cai Lun as “inventor” vs “refiner” |

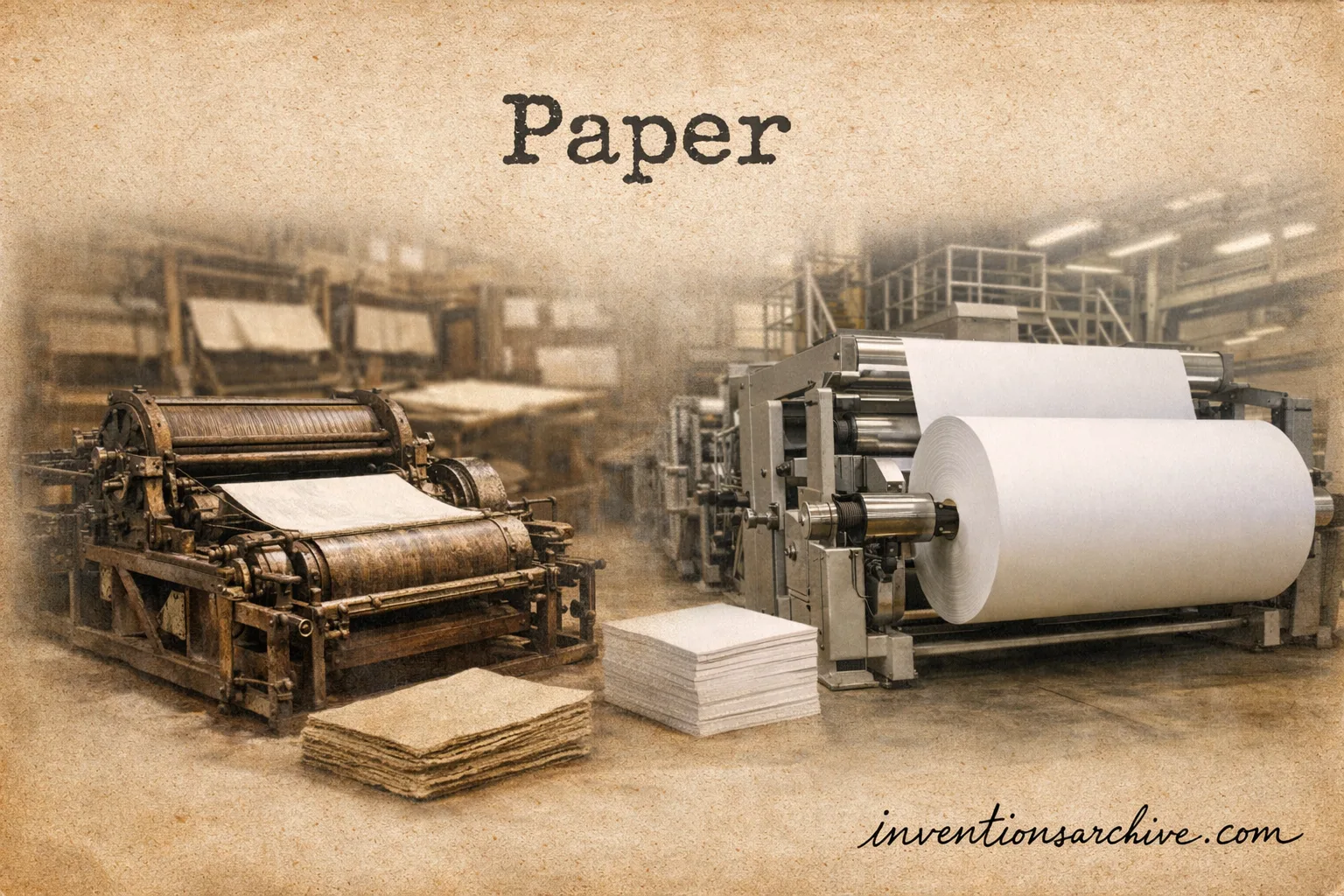

| Precursors + Successors | Papyrus, parchment, bamboo, silk → rag paper → wood-pulp paper → archival papers |

| Varieties Influenced | Writing papers; print papers; tissue; board and cartons; security papers |

Paper looks simple, yet it is a highly engineered fiber sheet. Its strength comes from tiny plant fibers locking together in a thin layer. That single idea—a portable surface that can hold ink, pigment, and meaning—shaped records, books, and everyday packaging.

Contents

What Paper Is

Paper is a mat of fibers pressed into a thin sheet. Those fibers mostly come from plants, so the backbone is cellulose. When the water drains away, the fibers settle, overlap, and create many contact points. The result feels light, yet it can be surprisingly tough.

Two details help explain paper’s everyday magic. First, the sheet is full of tiny gaps, so it can hold ink and still dry fast. Second, makers can tune how the sheet behaves with surface treatments and coatings, which change smoothness, absorbency, and brightness. That is why newspaper and photo paper feel nothing alike.

What Makes Paper Special

- Light to carry, easy to stack, easy to cut

- Scales well: from one note to millions of pages

- Custom surfaces: rough, smooth, glossy, matte

- Multiple jobs: writing, printing, wrapping, filtering, insulating

Origins and Early Evidence

The earliest widely discussed evidence places paper in China well before it became a common writing surface. A Smithsonian account notes paper in the 2nd century BCE as a packaging material, with paper starting to replace bamboo strips and becoming broadly used for writing by the 3rd–4th centuries CE.Details

Many histories credit Cai Lun, a Han court official, with presenting a refined process in 105 CE. One documented description lists inputs such as tree bark, hemp remnants, cloth rags, and fishing nets.Details

That attribution does not erase earlier finds. It highlights something practical: making a usable sheet is one challenge, and making it repeatable is another. The moment paper became reliable, it could move from special cases into routine records and daily trade.

How Paper Works

Paper begins as a fiber suspension in water. As the water drains, fibers settle into a layer. Drying turns that wet layer into a sheet because fibers cling at countless points. Those contacts create strength without adding weight, which is why a thin page can still resist tearing in normal use.

The sheet can also be tuned for its job. A writing paper often needs controlled absorbency, so ink sits cleanly instead of feathering. A packaging grade may favor bulk and stiffness. A tissue sheet values softness and easy folding.

Fiber Network

Long fibers usually add flexibility and tear resistance. Short fibers often improve smoothness and print detail.

Surface Behavior

Sizing and coatings influence ink holdout and feel. The same fibers can produce very different experiences.

Fiber Sources and Technologies

Early papermaking relied on available fibers. Historical descriptions connected with the 105 CE attribution mention inputs like bark, hemp, rags, and nets, all of which can be processed into a strong sheet.Details

Over time, papermaking expanded into a wide set of raw materials, including textile rags, agricultural residues, and later wood. Each source changes the balance between strength, opacity, and longevity.

Fiber choice also shapes what paper does best. A page built around long cellulose chains tends to stay flexible longer. A sheet dominated by shorter fibers can print sharply, yet it may feel more brittle with age. Composition quietly decides a lot about the life of a document.

How Paper Spread

Once paper proved reliable, it traveled through networks of exchange—people, skills, and finished sheets moving between regions. A broad pattern emerges: paper use and paper-making knowledge expanded across Asia, then reached the Mediterranean world, and finally became a European industry with dedicated mills.

A Metropolitan Museum of Art account summarizes a key European timeline: a paper mill in Spain (1151), followed by spread to France (1189) and Germany (1320). It also notes that the Gutenberg printing press increased paper demand.Details

From that point, paper became a standard platform for contracts, instruction, and communication. It also became a baseline material for labels and packaging as trade grew more complex.

Related articles: Adding Machine [Renaissance Inventions Series], Parachute (Leonardo da Vinci concept) [Renaissance Inventions Series]

Paper Types and Variations

Paper is not one thing. It is a family of engineered sheets tuned for different tasks. Variation comes from fiber choice, sheet structure, and surface treatment.

Main Paper Families

| Family | Common Traits | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Writing & Print | Controlled absorbency; readable surface | Books, forms, letters |

| Packaging | Stiffness; tear resistance | Cartons, bags, labels |

| Tissue | Soft; high porosity | Hygiene, cleaning |

| Board | Thicker layers; rigid feel | Boxes, book covers |

| Specialty | Tailored chemistry; precise performance | Filters, security papers, art papers |

Structural Variations

- Laid vs Wove: visible line pattern vs smoother, more uniform appearance

- Coated vs Uncoated: smoother print surface vs more natural texture

- Unbleached vs Bleached: natural tone vs brighter white, depending on grade

- Acid-Free Grades: designed for longer life in storage and libraries

These categories overlap. A single product might combine strong long fibers with a smooth coating, or mix fibers to balance print clarity and durability.

Paper Aging and Longevity

Paper can last for centuries, yet some modern sheets become brittle in decades. A Library of Congress preservation overview ties longevity to fiber composition and storage conditions. It notes that before the mid-19th century, many Western papers were made from cotton and linen rags, often retaining long fibers and staying durable. It also explains that as wood replaced rags, fiber length and chemistry shifted in ways that can speed aging.Details

“Yellowing” and “brittleness” usually trace back to chemistry, not mystery. When acids build up, they can shorten cellulose chains over time. That makes the sheet feel less flexible and more likely to crack at folds. A page that stays soft and springy often has a more stable balance of fibers and additives.

Why Old Paper Can Look Better

Rag-based sheets often start with longer fibers. They can stay strong and foldable for a long time.

Why Some Modern Paper Ages Fast

Acid formation can shorten fibers over time. The sheet may turn more brittle, especially at edges and folds.

Paper In Society

Paper supported the quiet infrastructure of everyday life: receipts, inventories, contracts, and letters. These documents are not glamorous, yet they make large systems work. A page can travel farther than a voice, and it can hold detail longer than memory.

Printing pushed paper into a new role: a platform for mass copying. Once pages could be reproduced reliably, paper became the default carrier for instruction, reference, and learning. That shift is visible in everything from schoolbooks to forms that standardize how information is stored.

Paper also shaped creative work. It can accept ink, graphite, paint, and printmaking techniques. Its surface can be smooth like glass or toothy like cloth. Artists treat it as both tool and material.

FAQ

Who invented paper?

Many histories credit Cai Lun with presenting a refined papermaking process in 105 CE. At the same time, evidence suggests earlier paper-like sheets existed, so the story is often framed as refinement and standardization rather than a single first moment.

What is paper made of, in simple terms?

Most paper is made from plant fibers rich in cellulose. Those fibers form a thin network as water drains away, and the dried sheet becomes stable through many fiber-to-fiber contacts.

Why do some books turn yellow and brittle?

Paper aging often relates to acid buildup and changes in the fiber structure. As cellulose chains shorten, the sheet can lose flexibility and feel stiffer. Some modern wood-based papers are more prone to these shifts than long-fiber rag papers.

What does “acid-free” mean?

Acid-free usually refers to paper manufactured to avoid strong acidic conditions that speed aging. Many archival-grade papers also include an alkaline reserve intended to help neutralize acids that form over time, supporting longer storage life.

How is paper different from papyrus and parchment?

Paper is a fiber sheet made by forming and drying a layer of plant fibers. Papyrus is built from layered plant strips, and parchment is made from prepared animal skin. All can carry writing, yet their structure and feel are fundamentally different.

Why are there so many kinds of paper?

Changing the fiber mix, the sheet structure, and the surface treatment creates different results. That flexibility lets paper serve many roles, from high-detail printing to protective packaging and soft tissues.