| Invention Name | Pythagorean Theorem |

|---|---|

| Short Definition | a2 + b2 = c2 (right triangles) |

| Approximate Date / Era | c. 1800–1600 BCE ApproximateDetails |

| Geography | Mesopotamia; later Greek tradition |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Anonymous; Pythagorean school (attribution) |

| Category | Mathematics; Geometry; Measurement |

| Importance | Distance in space Foundation for geometry & trigonometry |

| Need / Origin | Accurate lengths, diagonals, surveying, design |

| How It Works | Squares on legs add to square on hypotenuse |

| Material / Tech Basis | Number systems; geometric area reasoning |

| Early Use Context | Tablets; teaching; practical measurement |

| Spread Route | Ancient Near East → Mediterranean scholarship |

| Derived Developments | Coordinate distance; vector geometry; analytic geometry |

| Impact Areas | Education; engineering; architecture; navigation; computing |

| Discussions / Views | Named for Pythagoras; earlier knowledge documented |

| Predecessors + Successors | Diagonal rules → Euclidean proofs → modern linear algebra |

| Key Cultures | Old Babylonian; Greek mathematicians |

| Influenced Variants | Pythagorean triples; 3D distance; inner product spaces |

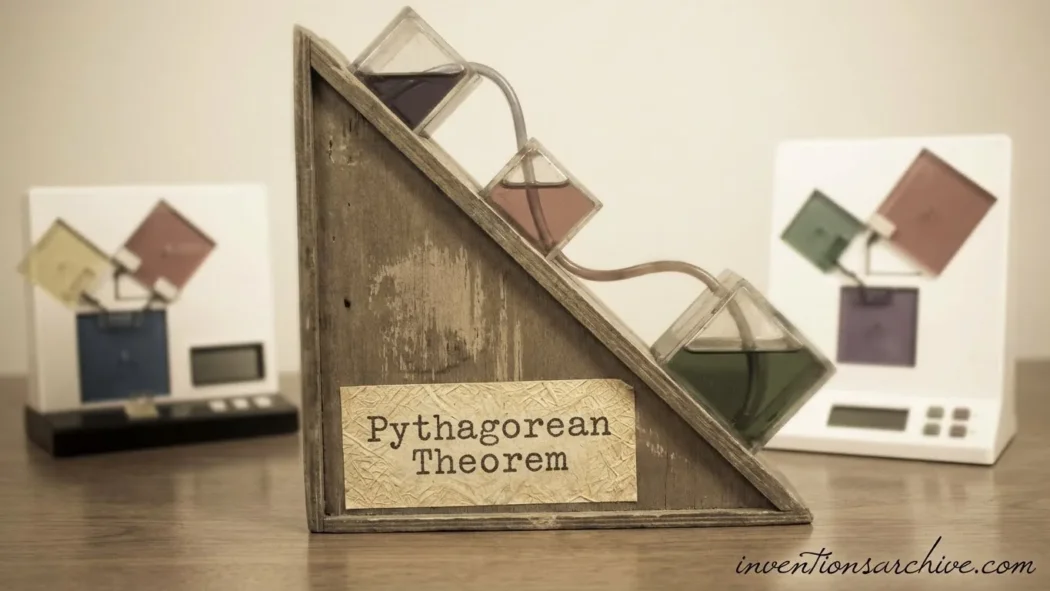

The Pythagorean theorem is a quiet powerhouse: one clean relationship that makes right triangles measurable and turns geometry into something you can compute. In its classic form, the squares on the two shorter sides add up to the square on the hypotenuse: a2 + b2 = c2.Details

Table Of Contents

What It Is

A right triangle has one angle of 90°. The side opposite that angle is the hypotenuse, and it is always the longest side. The theorem links all three side lengths with a single equation: a2 + b2 = c2, where c is the hypotenuse.

Plain meaning: the area of the square on the hypotenuse matches the combined areas of the squares on the two legs. That “area view” is why the theorem feels so stable across centuries.

Early Evidence and Timeline

The name points to Pythagoras, yet the idea is older. An Old Babylonian tablet known as YBC 7289 records a remarkably accurate value tied to the diagonal of a square, a setting where the same relationship appears naturally.Details That places clear evidence in the period c. 1800–1600 BCE.

Another famous source is Plimpton 322, a tablet that lists number patterns strongly connected to what modern readers call Pythagorean triples.Details It shows that people were working with structured right-triangle data long before later textbook phrasing existed.

Greek mathematics later gave the theorem a proof-centered identity. Writing is thin on exactly who proved what, and sources note that the theorem was known earlier while Pythagoras (or his school) may be linked to early proof traditions.Details The modern result remains the same: a precise rule for right-triangle measurement.

How The Theorem Works

Geometry View

Picture a square built on each side of a right triangle. The theorem says the two smaller squares’ areas add to the large square’s area. That turns a length question into an area balance.

Numbers View

- If a and b are known, then c = √(a2 + b2).

- If c and one leg are known, the other leg is found by rearranging the same equation.

- Scaling a triangle by a factor k scales all lengths by k, while squared lengths scale by k2.

A key detail stays constant: the theorem belongs to right angles. The moment the angle changes, the relationship changes too. That clarity is part of its lasting value.

Modern Forms and Meanings

The theorem is often learned in triangles, then reappears in modern math with new clothes. In many settings, it is really a statement about distance, orthogonality, and the way squared lengths combine in Euclidean space.

| Context | Equivalent Form | What It Says |

|---|---|---|

| Coordinate Plane | d = √((x2−x1)2 + (y2−y1)2) | Distance comes from perpendicular steps |

| 3D Space | d = √(dx2 + dy2 + dz2) | Same idea with one more axis |

| Vectors | |u+v|2 = |u|2 + |v|2 (when u·v=0) | Squared lengths add for perpendicular directions |

| Trigonometry | sin2θ + cos2θ = 1 | Unit-circle version of the same structure |

Why Squared Lengths Matter

Squared lengths behave smoothly: they avoid sign issues, they pair well with areas, and they connect to the dot product in vector geometry. That is why the theorem powers so many clean formulas for measurement.

Triples and Variations

Some right triangles have side lengths that land neatly on whole numbers. A set of positive integers (a, b, c) that satisfies a2 + b2 = c2 is called a Pythagorean triple. The best-known example is 3–4–5.

Primitive and Non-Primitive

A triple is primitive when the three numbers share no common factor greater than 1. Non-primitive triples are clean scalings of primitive ones, keeping the same shape while changing size.

Integer, Rational, Real

The theorem works over real numbers without any special conditions. Integer and rational cases stand out because they connect geometry to number patterns, a bridge that keeps inspiring mathematical culture.

Common Variants That Stay Close

- Converse (reverse test): if a2 + b2 = c2, the triangle is a right triangle.

- Distance between points: the coordinate formula is the theorem in disguise, written for perpendicular directions.

- Perpendicular components: in vectors, orthogonal parts combine by adding squares, not raw lengths.

Where It Shows Up

Once “distance from perpendicular pieces” becomes familiar, the theorem starts appearing everywhere. The context changes, the underlying shape stays: two independent directions, one combined resultant length.

- Architecture and construction: checking right angles, diagonal measurements, rectangular layouts.

- Engineering design: component lengths, orthogonal forces and displacements (in the simplest linear settings).

- Computer graphics: pixel-to-pixel distance, screen geometry, vector norms.

- Navigation and mapping: short-range planar approximations, coordinate offsets, grid-based distance.

- Everyday measurement: ladders, ramps, diagonals, and anything shaped like a right triangle.

Common Misunderstandings

Not Every Triangle

The equation a2 + b2 = c2 is specific to a right angle. For other angles, the relationship includes an angle term and becomes a different formula.

Units Stay Squared

When lengths are in meters, squared lengths are in square meters. The theorem lives naturally in squared quantities, then returns to a length when a square root is taken.

One more subtle point: the theorem measures straight-line distance in flat Euclidean settings. On strongly curved surfaces, distance behaves differently, which is why geometry has multiple flavors. The classic Pythagorean form remains the benchmark for flat space.

FAQ

Is the Pythagorean theorem only about triangles?

Its most familiar home is the right triangle, yet it also describes distance in coordinate systems and orthogonal components in vector geometry.

Why are squares used instead of plain lengths?

Squared lengths connect cleanly to area and behave well under algebra. That is why a2 + b2 is the natural pairing for the hypotenuse square c2.

What makes a “Pythagorean triple” special?

A Pythagorean triple uses integers for all three sides while still satisfying a2 + b2 = c2. These triples sit at the intersection of number patterns and geometry.

Does the theorem help in 3D space?

Yes. In three dimensions, perpendicular steps along x, y, and z combine as d = √(dx2 + dy2 + dz2), a direct extension of the same idea.

Is it accurate to say Pythagoras “invented” the theorem?

The theorem carries his name, while evidence shows earlier knowledge in ancient sources. Many accounts link Pythagoras or his school to early proof traditions, even as the underlying relationship is older.