| Invention Name | Mechanical Bell Tower (Tower Clock With Bell Mechanism) |

|---|---|

| Short Definition | A building-scale clock system that uses gears and a regulated oscillator to announce time by striking bells. |

| Approximate Date / Period | Late 13th–17th centuries (Approximate) |

| Date Certainty | Approximate for origins; More certain for later refinements |

| Geography | Europe (monastic and civic centers), later global |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Anonymous / collective (early clockmakers, founders, and builders) |

| Category | Timekeeping • Public communication • Urban infrastructure |

| Importance |

|

| Need / Why It Emerged | Reliable schedules for worship, work, markets, and civic life |

| How It Works | Power moves gear trains; a regulator sets the pace; a striking system triggers a hammer on a bell |

| Materials / Technology Base | Iron frames • brass wheels • stone towers • bronze bells |

| First Use Context | Bell ringing for hours and services; later public time dials |

| Spread Route | Regional adoption across cities and monasteries, then standard civic feature |

| Derived Developments | Chiming patterns • carillons • accuracy upgrades (pendulum, improved escapements) |

| Impact Areas | Commerce • education • craft • daily routines |

| Debates / Different Views | Origins and “first” claims vary (records differ by place and definition) |

| Precursors + Successors | Precursors: sundials, water clocks, manual bells • Successors: pendulum turret clocks, electro-mechanical drives, quartz control |

| Influenced Variants | Hour-strike clocks • quarter chimes • carillons • synchronized dial networks |

A mechanical bell tower is more than a clock in a high room. It is a public time system designed to be heard. Inside the tower, gears turn with steady intention, and a striking mechanism translates motion into sound. The result is simple for listeners: time becomes audible across streets, fields, and courtyards.

Table Of Contents

What It Is

A mechanical bell tower is a tower that houses a turret clock and a bell system meant for time announcement. The clock’s job is not only to keep time, but to broadcast it. That is why many early tower systems were designed around striking first, and visual dials later.

A Clear Working Definition

- Mechanical time base: gears and a regulator set the pace

- Public output: one or more bells are struck on a schedule

- Architectural integration: built for tower mounting and long duty cycles

- Human-scale benefit: time is shared without personal devices

Many towers also include a dial train that drives hands on exterior faces. Still, the defining feature remains the audible signal. A bell strike is a time stamp that reaches people who cannot see the tower at all.

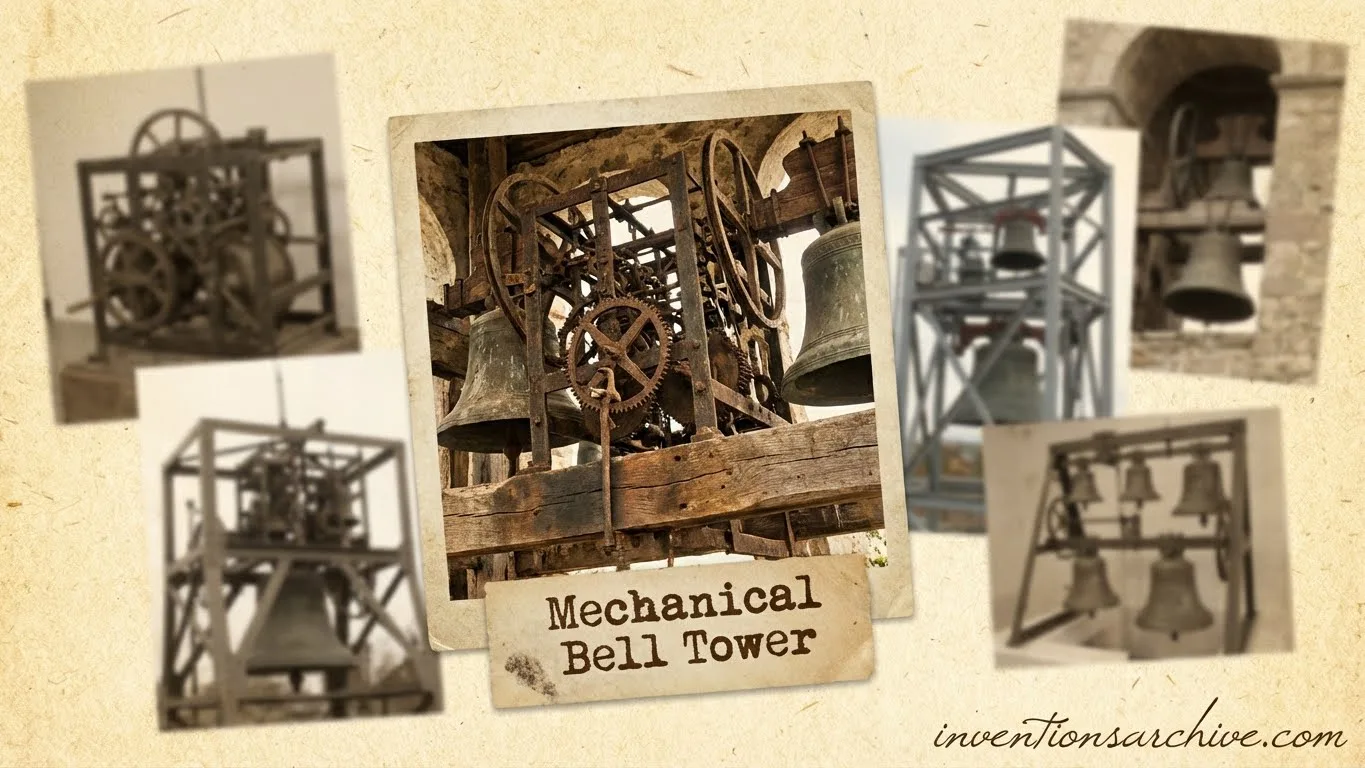

Core Parts Inside The Tower

Behind the stone and timber, the system is built from repeatable modules. Each module has a clear role, and together they form a mechanical language of time: power, regulation, display, and sound.

Power and Drive

- Weights (gravity) as the classic power source

- Barrels, drums, and cords/lines for controlled descent

- Maintaining power in some designs to reduce interruptions

Regulation and Timekeeping

- Escapement to meter energy in steps

- Oscillator (balance, foliot, pendulum) to set rate

- Gear ratios to translate steps into hours and minutes

Striking and Sound

- Striking train to count and deliver blows

- Hammer or external striker to hit the bell

- Governor (often a fly) to keep strikes evenly spaced

Some towers add a separate chiming train for melodic patterns, while the hour strike remains a counted signal. The architecture inside the room often looks bold and spare: thick frames, large wheels, and serviceable geometry.

Early Evidence and Timeline

When “first” is discussed, definitions matter. A bell-striking system can exist without a dial, and a clock can be recorded without describing its full mechanism. An English documentary record notes that in 1283 a clock was made to stand over the pulpitum at Dunstable Priory, interpreted as an early record of an escapement-controlled clock, with some uncertainty about form.Details

On a broader timeline, NIST describes the first truly mechanical clock resembling today’s timekeeping devices as emerging in Europe in the 14th century, and notes early performance around 15 minutes per day in accuracy—impressive for the era, yet still very coarse by modern standards.Details

| Phase | What Changed | What Listeners Heard |

|---|---|---|

| Early Tower Clocks (Approx.) | Weight power, simple regulators, strong frames | Hours struck for shared schedules |

| Refined Striking | More dependable counting and controlled pacing | Cleaner sequences and repeatable patterns |

| Higher Accuracy | Improved regulation, including the pendulum era | More trustworthy time signals across the day |

| Electro-Mechanical Additions | Motors, electrified winding, and remote synchronization | Consistent chimes with less manual intervention |

Why Bell Time Came First

In a dense town or a wide rural parish, a bell is a distance tool. A face is local; a strike carries. That single design choice helps explain why a mechanical bell tower became a public fixture even when personal timepieces were rare.

Bell Signaling Inside The Tower

Bell signaling depends on two promises: the clock must know when an hour arrives, and it must count reliably. That second promise is the heart of striking work. It is not just “ring a bell,” but “ring the correct number of times, at a controlled pace.”

How Striking Keeps Count

- Trigger: the time train releases the strike at set moments

- Counting: a countwheel or rack system determines the number of blows

- Pacing: a fly governor spaces the blows so the sound stays even

- Reset: the mechanism returns to a ready state for the next event

A British Museum horology record describes a clock with a verge escapement and an hour-only striking train, including elements like a countwheel and a fly governor—components that mirror the logic used in tower striking systems, even when scaled differently.Details

Related articles: Treadwheel Crane [Medieval Inventions Series], Mechanical Clock [Medieval Inventions Series]

Two Common Bell Arrangements

- Fixed bell, moving hammer: the bell stays still; an external hammer strikes it for a crisp, controlled note

- Swinging bell: the bell moves through an arc; time-strikes can be coordinated with an added hammer or a dedicated striking point

Large towers often combine signals: hour strikes, quarter patterns, and sometimes melodic sequences. That layered sound is not decoration alone. It is information carried by rhythm.

Types and Variations

The phrase “mechanical bell tower” covers a family of designs. The differences usually come from regulation, power, and the style of sound. Each type keeps the same goal: public time, made dependable.

By Regulator

- Verge-and-foliot era: early mechanical regulation, robust and simple in concept

- Pendulum era: improved steadiness and accuracy, especially for large stationary clocks

- Later precision systems: refined escapements and controlled energy delivery for stable operation

By Sound Output

| System | What It Plays | Typical Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Hour Strike | Counted hour blows | Striking train + countwheel/rack + hammer |

| Quarter Chimes | Short patterns at quarter hours | Chiming train with timed releases |

| Carillon | Full melodies and repertoire | Multiple tuned bells linked to a console |

A carillon is usually defined as a set of at least 23 tuned bells, typically played from a console of wooden batons and pedals. That design turns the tower into an instrument, not only a signal.Details

By Power and Automation

- Weight-driven: classic gravity power, often with large descending weights

- Spring-driven (later, smaller contexts): compact power storage for certain installations

- Electro-mechanical support: motors for winding, plus timed electrical control while keeping the historic movement intact

Materials and Engineering Choices

Mechanical bell towers are built for endurance. Large components spread load, reduce stress, and tolerate long duty cycles. Frames are often iron or steel; wheels are commonly brass; pivots and pinions may use hardened alloys. Bells are typically bronze, chosen for tone and structural stability. The tower structure itself acts as a sound projector.

Why Towers Suit Mechanical Clocks

- Space: room for large wheels, long pendulums, and hanging weights

- Stability: reduced vibration improves consistent regulation

- Reach: height gives bells a wider audible range

- Access control: a dedicated clock room protects delicate parts

Legacy In Daily Life

The mechanical bell tower shaped how communities experienced time. It created a shared reference point, repeated day after day, year after year. The sound of a strike is a public contract: time is agreed, and it is heard. This is why tower clocks became a quiet form of infrastructure, as familiar as a road sign.

Pendulum clocks, introduced by Christiaan Huygens in 1656, became the most accurate form of timekeeper available until quartz clocks appeared in the 1930s. That long span of dominance explains why upgraded regulation mattered so much for towers that served as local standards.Details

Where The Invention Still Shows Up Today

- Heritage towers that still strike hours with original or restored movements

- Modernized towers using electric winding while preserving mechanical character

- Carillon towers that blend music and time signals in a single structure

- Public soundscapes where chimes remain a gentle civic presence

FAQ

What Makes A Bell Tower “Mechanical”?

A bell tower is mechanical when the timing and bell strikes come from gears, a regulator, and a striking system that counts blows. The key idea is self-acting time signaling, not manual ringing.

Is A Tower Clock The Same As A Mechanical Bell Tower?

A tower clock is the timekeeping machine. A mechanical bell tower includes that machine plus the bell output designed to announce time to the public.

Why Did Some Early Systems Strike Bells Before They Had Large Dials?

Sound travels where sight cannot. A bell strike delivers time information to anyone within earshot, even if the tower face is not visible. That makes audible time a practical first step for public service.

What Is The Difference Between Chimes and A Carillon?

In common usage, chimes often refer to smaller sets of bells used for patterns, while a carillon is a larger tuned set that supports a wide musical range. A carillon also uses a dedicated console that gives performers expressive control.

How Were Mechanical Bell Towers Powered Before Electricity?

Most classic installations used weights and gravity. Energy moved through gear trains, and the regulator set the clock’s pace. Later systems added electrical assistance for winding or synchronization while the mechanical logic remained recognizable.