| Invention Name | Cornelis Drebbel’s Submarine (“Diving Boat”) |

|---|---|

| Short Definition | Leather-sealed wooden submersible rowed from inside for underwater travel |

| Approximate Date / Period | 1620 (Reported) • 1620s development (Approximate) |

| Geography | London • River Thames • England |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Cornelis Drebbel • Dutch inventor working in England |

| Category | Navigation • Engineering • Transport |

| Importance (Why It Matters) |

|

| Need / Motivation | Underwater navigation idea • controlled submersion challenge |

| How It Works | Oars via sealed ports • ballast for depth • air refresh methods |

| Materials / Technology Base | Wood frame • watertight leather • grease-sealed joints |

| First Known Setting | River trials • public demonstrations • Thames |

| Spread / Influence Path | European discussion • later inventors • submersible tradition |

| Derived Developments | Watertight “penetrations” • snorkel-like thinking • life-support focus |

| Impact Areas | Engineering • maritime science • navigation • design history |

| Debates / Different Views | Date details (Approximate) • air method (Disputed) • passenger claims (Varies) |

| Precursors + Successors | Diving bells → Drebbel submersible → later submarines |

| Key People / Institutions | King James I • Royal Navy trials • Thames spectators |

| Notable Variants | Rowboat-based • multi-oar versions • tube-supported airflow concepts |

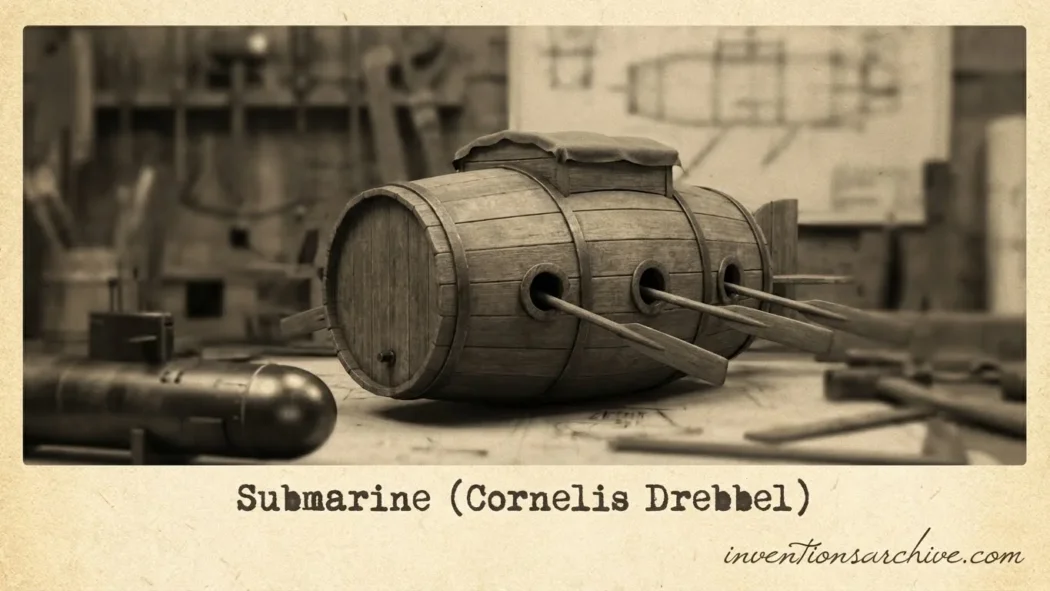

Cornelis Drebbel’s submarine sits at a rare crossroads of craft and science. It was a wooden, leather-sealed submersible that proved people could move, steer, and stay underwater with real control.

Table of Contents

What It Is

Drebbel’s craft is often described as an early navigable submarine, sometimes called a diving boat. Think of a reinforced boat that could be sealed well enough to submerge, travel, and resurface on purpose—without becoming a rigid “capsule” like later deep-sea vehicles.

One well-known summary places this breakthrough in 1620, noting a wooden submarine built for King James I and rowed through sealed ports using waterproofed leather sleeves, with airflow supported by periodic air-refresh measures. Details

Core Identity

- Human-powered propulsion (oars)

- Watertight hull covering (leather over wood)

- Depth control through ballast ideas

- Air management that kept crew breathing for extended periods

Early Evidence and Timeline

Almost everything known comes from accounts, not surviving blueprints. Still, the repeated details line up: a rowboat-like hull, oars through sealed openings, and a workable way to refresh air.

| Time | What’s Reported | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1604 (Background) | Drebbel in England under royal patronage | Resources and workshop support |

| 1620 (Reported) | First “diving boat” completed; oar propulsion; leather sealing | Early navigable submersion |

| 1620s (Approximate) | Multiple trials and refinements in the Thames | Repeatability, not a one-time stunt |

A widely cited description says the diving boat was sealed with a covering of greased leather and could travel the River Thames at about 12–15 feet depth, using air tubes with floats to keep their ends above water. Details

How It Worked

The engineering problem was simple to state and hard to solve: keep water out, allow motion, control depth, and manage breathable air. Drebbel’s submarine matters because it tackled all four at once, in a form people could actually use.

Hull and Seals

The core structure is described as a wooden frame covered with watertight leather. That covering acted like an early flexible skin, helping close gaps where planks and joints would otherwise leak.

- Leather covering over wood

- Grease and compression to improve sealing

- Sealed openings where parts passed through the hull

Propulsion and Steering

Contemporary retellings emphasize oars worked from inside the hull. The trick was letting oars move while keeping water out—often described with watertight sleeves or sealed ports.

- Oar-powered movement

- Leather sleeves or seals at each oar port

- Rudder control for direction

Buoyancy and Ballast

To go down, the craft had to become slightly heavier than the water it displaced. A clear, practical description says water-filled bladders (a form of ballast) helped the submarine descend, and squeezing water back out helped it surface. Details

| Control | Simple Meaning | What It Enables |

|---|---|---|

| Ballast In | Add water weight | Controlled descent |

| Ballast Out | Remove water weight | Reliable surfacing |

| Trim | Balance front/back | Stable travel |

Air Supply and Time Underwater

Air is the make-or-break detail for a crewed submersible. One account describes snorkel-like tubes bringing in fresh air, while other summaries mention air-refresh methods to keep the space breathable. The same set of reports includes a striking benchmark: about three hours submerged at roughly 15 feet depth during Thames trials.

Design Variations

Many retellings speak of multiple versions, growing in size as confidence rose. A museum account states Drebbel built three working submarines and describes a final model with six oars and capacity for up to 16 men, using air tubes held above the surface with floats. It also notes real uncertainty around finer points, including how the air was truly managed and whether a royal ride happened as later stories claim. Details

What Likely Changed Between Builds

- More crew → more power from oars

- More volume → more air capacity and stability

- Refined seals → fewer leaks at moving parts

- Better trim → smoother underwater travel

Related Early Underwater Ideas

Drebbel’s submarine belongs to a wider family of underwater tools. Diving bells aimed to keep a pocket of air in place. Drebbel’s leap was adding mobility and steering, turning “staying down” into “going somewhere.”

- Diving bell → stationary air pocket

- Submersible boat → air + motion

- Later submarines → stronger hulls and new propulsion

Why It Mattered

The value of Drebbel’s submarine is not just that it went underwater. It combined several “firsts” in a single working system: watertight motion, stable depth control, and the practical problem of human survival in a sealed space.

Lasting Ideas That Still Read Modern

- Sealed penetrations (oars through a hull) as a design discipline

- Ballast logic for depth and trim, not just sinking

- Air management as a core system, not an afterthought

- Testing in real water, with repeat trials and refinements

Even when details vary across sources, the overall picture stays consistent: a workable underwater vehicle emerged in the early 1620s, in a busy river setting, using simple materials pushed to their limit—wood, leather, grease, and careful sealing.

FAQ

Was Drebbel’s submarine really underwater and navigable?

Several independent summaries describe a wooden, leather-sealed craft that could submerge, travel, and resurface under control. Reported depths cluster around 12–15 feet, with reported durations reaching hours in some retellings.

How did it move underwater?

The consistent answer is human power. Oars were worked from inside the hull through sealed openings, often described with leather sleeves or similar seals to limit leakage.

How did it control depth?

A clear, widely repeated mechanism is ballast: taking in water to descend, then forcing it out to rise. That basic buoyancy logic remains at the heart of many later underwater designs.

How did the crew breathe inside?

Air supply is the most debated detail. Some descriptions mention snorkel-like tubes or air tubes supported by floats, keeping an opening above the surface. Other accounts describe air-refresh measures. The safest summary is that multiple explanations exist and the exact method is not settled.

How many people could it carry?

Some museum narratives describe later builds with higher capacity, including a reported version with six oars and space for up to 16 people. Because primary design records are not available, capacity figures are best treated as reported rather than perfectly measured.