| Invention Name | Heating Systems (Hypocaust) |

| Short Definition | Underfloor heating using hot air from a furnace |

| Approximate Date / Period | 2nd Century BCE–5th Century CE (Approximate) |

| Date Certainty | Approximate |

| Geography | Roman Mediterranean and northern provinces |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Roman engineering tradition (collective) |

| Category | Building technology, heating, public amenities |

| Importance |

|

| Need / Reason It Emerged | Warm interiors for bathing, living, and social spaces |

| How It Works | Furnace → underfloor void → wall flues → vent |

| Materials / Technology Basis | Terracotta, brick, stone piers, mortar, concrete |

| Early Use Contexts | Bath complexes, warm rooms, select residences |

| Spread Route | Italy → provinces (Britain, Gaul, Germany, beyond) |

| Derived Developments | Wall heating tiles, improved bath layouts, later radiant heating ideas |

| Impact Areas | Architecture, public health culture, education, craftsmanship |

| Debates / Different Views | Exact earliest date and “first site” remain discussed |

| Precursors + Successors | Precursors: braziers, hearths → Successors: modern underfloor heating |

| Key Places / Civilizations | Pompeii, Roman Britain, Roman urban centers |

| Influenced Variants | Pillar hypocaust, channel hypocaust, wall-flue heating |

Hypocaust heating was the Roman answer to a simple wish: warmth that felt steady, quiet, and built into the room itself. Instead of heating the air in one corner, it moved heat through a hidden network under the floor, and sometimes up the walls, turning baths and private interiors into spaces where comfort could be designed rather than hoped for.

Table Of Contents

What The Hypocaust Is

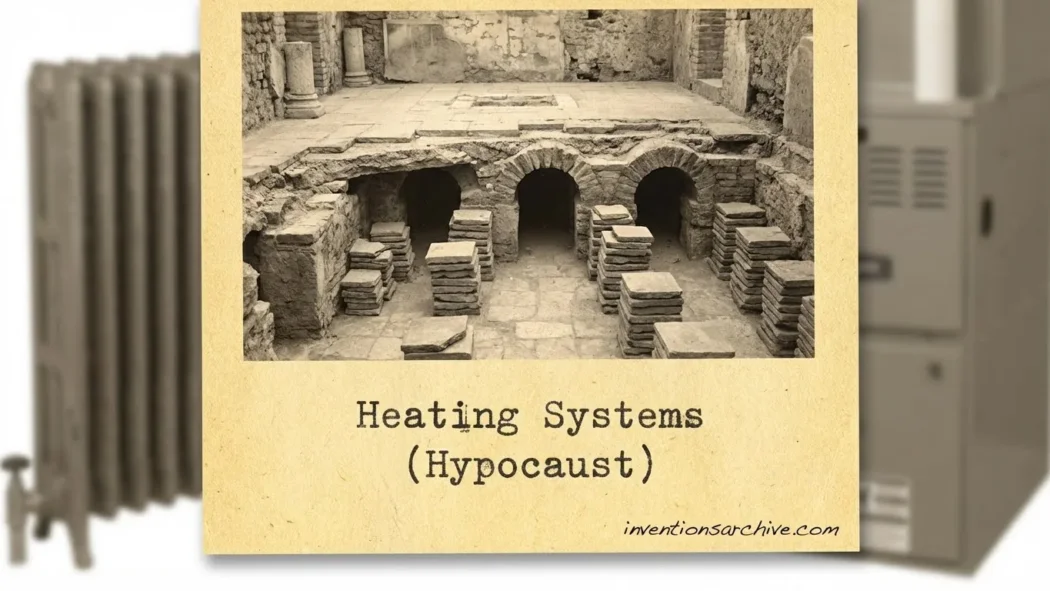

A hypocaust is an open space under a floor where heat from a fire or furnace moves through a hidden cavity and warms the room above. Romans developed it into a practical system for baths and, in many cooler regions, for private houses as well. Some buildings guided that heat into vertical wall paths, so warmth could rise and spread more evenly instead of pooling at floor level.Details

Key Terms Used In Hypocaust Heating

- Praefurnium : the furnace area that produces hot gases

- Pilae : small pillars that raise the floor, creating the underfloor void

- Suspensura : the “suspended” floor layer above the void

- Flue Tiles : hollow tiles that guide warm air up the walls

Early Evidence and Timeline

The hypocaust is strongly tied to bath culture because baths demanded reliable warmth: not just a hot room, but a sequence of spaces with different temperatures. In Pompeii, research on the Stabian Baths and Republican Baths highlights how early bath complexes were built in the 2nd century BCE and then developed in multiple phases, with careful attention to how their heating system worked alongside water collection and drainage.Details

- 2nd century BCE : large bath buildings in Pompeii are already established, forming a setting where structured heating becomes valuable

- Later centuries : hypocaust layouts spread widely, adapting to different plans and climates

- Archaeological survival : floors, tiles, pillar bases, and soot traces help reveal the heat paths today

How The Hypocaust Works

A hypocaust works like a guided heat river. Hot gases leave the furnace area and enter the underfloor void. The raised floor holds that heat long enough for the surface above to become pleasantly warm, then the air continues toward outlets, sometimes traveling up the walls through hollow tiles. The result is a room where heat feels distributed, not concentrated in one spot.

Heat’s Path

- Furnace produces hot gases

- Underfloor void channels heat under the room

- Wall routes (in some buildings) lift warmth upward

- Vents release spent air and smoke

Why It Feels Even

- Large surface area under the floor spreads warmth

- Thermal mass of tile and concrete stabilizes temperature

- Wall heating can reduce cold corners in tall rooms

Key Parts and Materials

What survives in a hypocaust is often the infrastructure rather than the finished room. Archaeology frequently reveals the brick supports and heat channels: square bricks used to build pilae (little columns), terracotta elements, and mortar traces. A Roman hypocaust brick in the British Museum is described as a square brick likely used for a pila, with a production range noted as 1st–5th century CE, illustrating how widely the system’s basic materials traveled and endured.Details

- Pilae stacks : small columns supporting the floor slab

- Underfloor cavity : the air space that carries heat

- Floor build-up : tile, concrete layers, then finish surfaces

- Wall heating options : hollow tiles or spaced wall systems for rising warmth

Types and Variations

“Hypocaust” is one idea with multiple layouts. Some designs rely on brick pilae like a miniature forest of supports; others guide heat through channels cut below the floor. Many bath buildings also pair underfloor heat with wall heating, so warmth rises through the room in a more balanced way.

| Variant | Heat Route | Typical Setting | Common Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pillar Hypocaust | Furnace → underfloor void | Bath hot rooms, warm rooms | Pilae bases, floor collapse layers |

| Channel Hypocaust | Furnace → trenches beneath floors | Selected houses, some public rooms | Linear channels, soot staining |

| Wall-Flue Heating | Underfloor → vertical tile flues | Rooms needing higher warmth | Hollow tiles, wall openings |

| Mixed Systems | Underfloor + wall paths | Large bath complexes | Multiple flue points, dense tilework |

Temperature Zoning In Bath Buildings

Roman bath layouts often emphasize a graded experience: warmer rooms placed closer to the heat source, cooler rooms farther away. This planning makes the hypocaust feel less like a single machine and more like a system that shapes movement, comfort, and the rhythm of the building.

Where It Was Used

Hypocaust heating appears most often in places where people expected steady warmth as part of daily life: baths, select urban buildings, and well-appointed residences. In colder regions, the system’s value becomes obvious: it turns stone and tile interiors into spaces that feel welcoming for longer periods of the year, without relying on a single open flame in the room.

- Bath complexes : warm and hot rooms benefit most

- Reception rooms : comfort for gatherings and conversation

- Regional adaptations : different tile choices, layouts, and airflow paths

A Clear Example In Roman Britain

In Verulamium Park, near the Verulamium Museum, a preserved hypocaust shows how warmth could travel beneath a floor and support a finished surface such as a mosaic. The site describes raised floors on brick columns or, in that specific example, heat trenches beneath the floor, and notes the structure is thought to have belonged to reception rooms in a large town house built around AD 200.Details

Legacy and Influence

The hypocaust’s lasting value is the idea it proves: heat can be distributed through a building’s structure, not just delivered by a visible flame. That principle echoes in later underfloor heating concepts, in the planning of temperature zones, and in the way modern buildings treat comfort as part of architecture, not an afterthought.

FAQ

Is a hypocaust the same as modern underfloor heating?

They share the same comfort logic: warmth rises from below and spreads across a wide surface. A hypocaust uses hot gases moving through an underfloor void, while many modern systems use warm water pipes or electric elements embedded in the floor structure.

Did hypocaust systems heat walls too?

Often, yes. Many buildings guided warm air into wall flues so heat could rise and reduce cold zones higher in the room. The exact method depends on the site and the building’s purpose.

Why are hypocausts so strongly linked to Roman baths?

Baths demanded predictable warmth across different rooms. A hypocaust can support that kind of temperature staging, making warm and hot rooms comfortable for longer periods without placing open flames inside the bathing spaces.

What parts of a hypocaust are most likely to survive today?

The most common survivors are the brick supports, underfloor void outlines, flue tiles, and soot traces that hint at airflow. Finished floors may survive too, especially if a site is preserved in place.

What fuels were used to generate the heat?

Fuel varied by region and availability. Archaeological contexts frequently point to wood and other local combustibles. The key point is that the fuel stays in the furnace area while the heat travels into the building.