| Invention Name | Flying Buttress |

| Short Definition | External masonry arch support that redirects vault thrust to an outer pier Details |

| Approximate Date / Period | 1170s onward Approximate Details |

| Geography | Île-de-France; later pan-European |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Anonymous master masons Collective |

| Category | Architecture; Structural Engineering |

| Importance |

|

| Need / Origin Problem | Outward thrust; wall cracking; height limits |

| How It Works | Compression arch carries thrust to outer pier |

| Material / Technology Base | Cut stone; lime mortar; gravity + compression |

| First Common Use | Rib-vaulted cathedrals; clerestory walls |

| Spread Route | N. France → England → Low Countries/Germany → Iberia/Italy |

| Derived Developments | Thinner walls; vast stained-glass bays; multi-tier supports |

| Impact Areas | Engineering; building safety; urban heritage; craft know-how |

| Debates / Different Views | Dating complicated by later rebuilding Touched-Up Evidence |

| Precursors + Successors | Solid buttress + hidden supports → visible flyers + pinnacled piers |

| Key Places / Traditions | Early Gothic workshops; major cathedral sites |

| Influenced Forms | External bracing ideas; buttressed halls; later masonry stabilization |

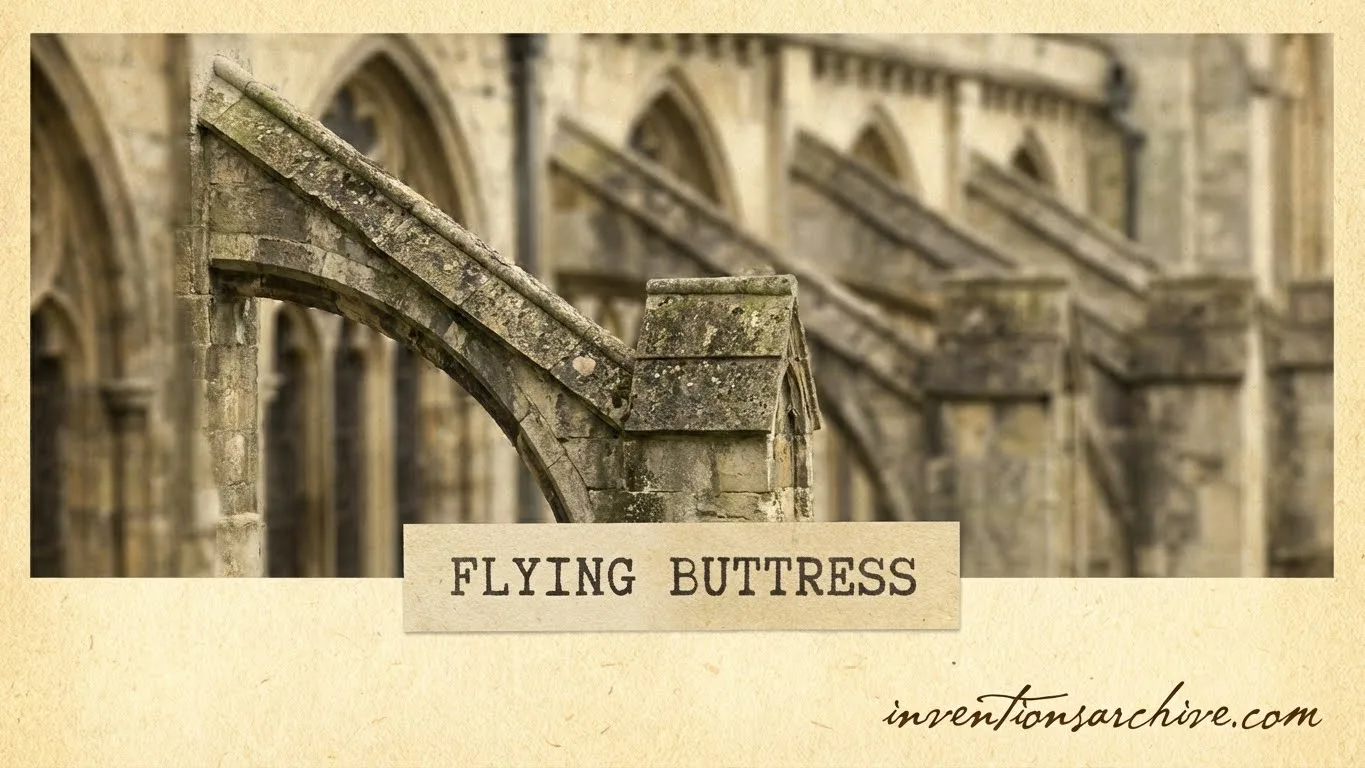

A flying buttress looks like a stone arm reaching out from a tall wall. Its real job is quietly managing force. By pushing the outward load from heavy stone vaults into an outer pier, it lets builders raise walls higher and open them with more glass, without turning the whole building into a thick block of masonry.

Table Of Contents

What A Flying Buttress Is

A flying buttress is an external support system made of masonry. The key idea is simple: instead of asking a tall wall to resist sideways pressure alone, the building sends that pressure through a stone arch into an outer mass designed to take it.

- Flyer: the arched “bridge” that carries load in compression

- Outer Pier: the heavy vertical support that receives the load

- Pinnacle (often): added weight that helps keep the pier firmly loaded

What It Is Not

- Not a solid buttress fused to the wall from ground to roof

- Not a decorative arch with no structural role

- Not a modern steel brace, even if the logic feels similar

Why It Was Needed

Stone roofs and vaults do not push only downward. They also push outward, creating horizontal thrust. When builders aimed for taller interiors, that sideways pressure could crack walls, distort arches, or demand walls so thick that windows became small. A flying buttress solved the conflict: strong walls and generous openings.

Engineering teaching materials describe the core problem clearly: pointed arches and ribbed vaults generate horizontal thrust, and flying buttresses divert those forces to the ground so the main walls can be lighter and more open Details. That shift changed what large masonry buildings could look like.

Early Evidence and Timeline

- Before visible flyers: thick walls, solid buttresses, and internal load paths carried much of the vault pressure

- Late 12th century: flying buttresses begin to appear as recognizable external systems

- 13th century: wider adoption, refinement, and more confident spacing between supports

- Later medieval period: multi-tier arrangements become common where loads and heights increase

One clear historical signal comes from high-stakes experimentation. The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes that flying buttresses appear in the 1170s, and it also points to the 1284 collapse at Beauvais as a reminder that height had real structural limits, followed by rebuilding supported by more flyers.

A Note on Dating and Restoration

Many famous cathedrals have been repaired or rebuilt over centuries. That is why scholars often discuss dates with care. A Columbia University teaching resource on Notre-Dame states that the physical evidence supports a 12th-century origin for the flyers there, even though the buttresses visible today were rebuilt later Details. This kind of layered history is normal in long-lived masonry monuments.

How The System Works

The structural story can be read as a clean path of forces. A vaulted ceiling pushes outward at its springing points. The flyer receives that sideways load and stays mostly in compression. The load then travels into the outer pier, which is heavy enough to channel it down into the ground.

Force Path in Plain Terms

- Vault pushes outward as well as downward

- Flyer carries the sideways load in compression

- Outer pier receives the load and sends it to the ground

- Wall can be slimmer, freeing space for larger windows

Key Parts and Materials

| Part | Main Role | Typical Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Flyer | Moves thrust outward | Stone arch in compression |

| Outer Pier | Receives + grounds forces | Mass masonry; deep footing |

| Pinnacle | Adds stabilizing weight | Vertical mass on pier head |

| Connection Points | Transfers load safely | Tight stone joints; robust bedding |

Most classic systems rely on cut stone and lime mortar. The geometry matters as much as the material. If the flyer’s line of thrust stays well within the masonry, the structure behaves with steady compression, which stone handles beautifully.

Types and Variations

There is no single universal shape. Builders adjusted span, angle, and mass to suit each site. Some designs look light and airy, others are thick and muscular. The shared idea is always the same: a controlled external path for sideways forces.

Related articles: Gothic Arch [Medieval Inventions Series]

| Variation | What Changes | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Tier Flyer | One arch to outer pier | Efficient for moderate thrust |

| Double-Tier Flyers | Two stacked arches | Handles higher walls and complex loads |

| Steeper vs. Flatter Flyers | Angle of the arch | Balances thrust direction and pier demand |

| Heavier Piers and Pinnacles | More vertical mass | Improves stability at the receiving end |

| Closer Spacing | More frequent supports | Reduces wall span under thrust |

How Variations Shape the Look

- Wide spacing can feel cleaner, but it demands stronger flyers and piers

- Dense spacing can look rhythmic, and it lowers stress per bay

- Pinnacles add a sharp silhouette while serving real structural purpose

Design Choices and Limits

A flying buttress is powerful, yet not magical. Its success depends on careful proportions, sound foundations, and steady masonry. Small shifts in settlement can change how thrust travels. Over long periods, weathering and repairs also matter, especially where joints and water-shedding surfaces meet.

What Builders Optimized

- Height without wall failure

- Light through larger openings

- Predictable load paths in stone

What Still Needed Care

- Foundations and soil stability

- Water control around joints and caps

- Repairs that keep load paths consistent

Where It Spread and Why It Lasted

Once the logic proved reliable, the flying buttress traveled with skilled builders and workshop knowledge. It supported bigger spans and higher clerestories, so it fit the ambitions of many major stone buildings. Even when later styles shifted, the idea stayed relevant: separate the support from the wall so the wall can become a lighter surface.

Legacy in Structural Thinking

Modern materials changed the details, yet the core concept still feels familiar. When engineers place support outside a main enclosure—through bracing, frames, or external stiffening—they echo the same ambition: keep the primary surface free for space, light, and function, while sending forces into a clear supporting system.

FAQ

Why Is It Called “Flying”?

The arch seems to “leap” across open space from the high wall to a separate pier. That visual gap is the signature feature, even though the masonry is firmly loaded in compression.

Did Flying Buttresses Replace Solid Buttresses?

They did not erase them. Many buildings combine solid buttresses with flyers, using each where it best fits the load path and the plan.

Do They Carry Weight or Only Sideways Force?

The main purpose is handling sideways thrust from vaults and arches. Some vertical load may also pass through parts of the system, yet the defining role is stabilizing outward pressure.

Why Do Many Have Pinnacles on Top?

A pinnacle adds downward weight to the outer pier. That extra weight helps the pier resist the incoming thrust and keeps the masonry working in compression.

Are All Famous Examples Original Today?

Many landmark buildings have experienced repair or rebuilding. That is normal for long-lived masonry, and it is one reason dating details can be discussed with care.