| Invention Name | Cement Mortar (Portland-cement mortar family) |

|---|---|

| Short Definition | Hydraulic binder + fine aggregate + water; masonry jointing material |

| Approximate Date / Period | Early 19th century origins; broader use early 20th century |

| Date Certainty | Approximate (material family evolves by place and standard) |

| Geography | Britain → Europe / North America → global |

| Inventor / Source Culture | Industrial Britain; key early figure: Joseph Aspdin (Portland cement era) |

| Category | Construction material; masonry; repair; finishing |

| Need / Driver | Faster set; predictable strength; durable joints |

| How It Works | Water-triggered hydration; hardening binder matrix |

| Materials / Technology Basis | Portland cement (or blended); sand grading; optional lime / admixtures |

| Early Use Cases | Masonry jointing; stucco / render; brickwork and blockwork |

| Spread Route | Trade + standardization + industrial production; import then local manufacture |

| Derived Developments | Bagged mortars; polymer-modified mortars; thin-bed systems |

| Impact Areas | Housing; infrastructure; restoration; materials science; education |

| Debates / Alternate Views | “Best” binder depends on masonry unit; vapor permeability vs strength |

| Precursors + Successors | Precursors: lime mortars, natural hydraulic limes; Successors: blended and engineered mortars |

| Key People / Cultures | Industrial cement makers; standards bodies; conservation professionals |

| Variations Influenced | Cement-lime mortars; masonry cement mortars; repair mortars; colored mortars |

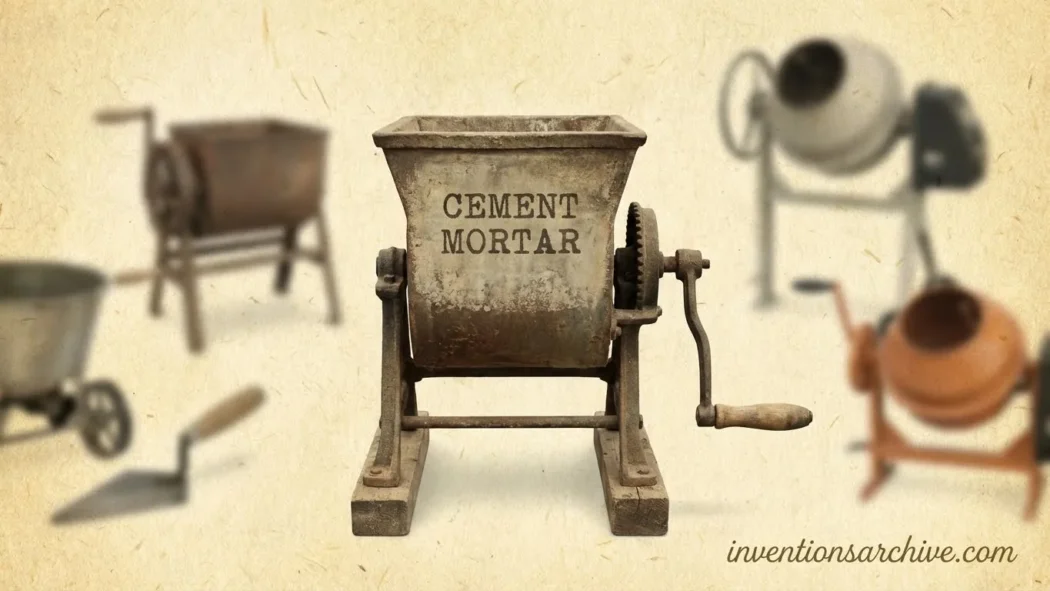

Cement mortar sits quietly between bricks and blocks, yet it shapes how long a wall feels solid, how clean a joint looks, and how a façade weathers over time. It is a family of materials built around hydraulic cement: add water, and chemistry begins. The result is a dense binder that grips sand, bonds masonry units, and forms a joint that can handle everyday movement while staying visually sharp.

Table of Contents

What Cement Mortar Is

Cement mortar is a paste-and-sand composite designed for masonry joints. The binder is typically Portland cement (sometimes blended), and the aggregate is fine sand. Once water is present, the binder hardens through hydration and locks the sand into a tight matrix. That matrix does two main jobs at the same time: it transfers load between units and it seals the joint against weather while still letting a wall “breathe” at a level that depends on the mix design and the masonry unit.

In everyday language, people treat cement and mortar as the same thing. They are not. Cement is the powder binder. Mortar is the working blend that includes sand and water, shaped for joints. That distinction matters because the behavior of the finished joint depends as much on sand grading and water retention as it does on the binder itself.

Where You See It

- Brick walls and veneers

- Concrete blockwork

- Stone masonry joints

- Exterior render and base coats

What It Must Do

- Create bond to units

- Hold joint shape with good workability

- Manage moisture: retain water while curing, resist washout

- Stay durable through weather cycles

Key Ingredients and Roles

Most cement mortars revolve around four essentials: cement, sand, water, and time. Yet the “feel” of mortar in the joint is shaped by subtle choices—sand grading, water retention, and optional additions like lime or plasticizers. Small changes can shift workability and long-term durability.

- Portland cement: the hydraulic binder that hardens with water.

- Sand: the skeleton; grading influences texture, shrinkage, and finish.

- Water: activates hydration; too little or too much changes pore structure and performance.

- Optional lime: often used to improve workability and water retention in many traditional masonry mortars.

- Optional admixtures: air entrainers, pigments, water repellents, or polymers—each changes one or more properties.

In the U.S. Geological Survey’s mineral industry reporting, hydraulic cement is broadly discussed in families that include Portland cement and masonry cement, both of which can be used as binders in mortar systems.Details That taxonomy matters because “cement mortar” is not one fixed recipe; it is a category shaped by binder choice, unit type, exposure, and specification method.

Mortar, Concrete, and Grout

These three materials share familiar ingredients, yet they are engineered for different roles. The easiest way to separate them is by aggregate size and intended placement. Mortar uses fine sand for joints and thin layers. Concrete introduces coarse aggregate for bulk structural mass. Grout is formulated to flow into voids and consolidate around reinforcement or within masonry cores.

| Material | Typical Aggregate | Primary Role | How It Is Placed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortar | Fine sand | Bonding + joint filling | Spread into thin beds and joints |

| Concrete | Sand + coarse stone | Structural mass + load carrying | Poured and consolidated |

| Grout | Fine filler (sometimes very small aggregate) | Void filling + anchorage | Flowed or pumped into spaces |

How Cement Mortar Hardens

Portland cement is described as a hydraulic cement because it gains strength through chemical reactions between cement and water, a process known as hydration.Details This is not drying. Water becomes part of the hardened structure, and moisture conditions during early curing strongly influence how the internal binder network develops.

At the heart of that network is calcium-silicate-hydrate—often shortened to C-S-H. It is widely described as the main product of Portland cement hydration and the primary contributor to strength in cement-based materials.Details In practical terms, as C-S-H forms and densifies, the mortar becomes less workable, sets, and then continues gaining strength.

Set vs Strength

- Setting: the shift from plastic to firm; joints hold shape.

- Hardening: continued hydration; strength rises over time.

- Moisture: supports hydration; overly dry conditions can reduce long-term performance.

Types and Variations

Cement mortar is not a single formula. It branches into families based on binder type, additives, and intended behavior. Some variants target workability for vertical joints. Others focus on durability for exposed faces. In conservation, compatibility with masonry units becomes the priority.

Portland Cement Mortar

This is the straightforward family: Portland cement as the primary binder with fine sand. It tends to develop higher compressive strength than traditional lime-only mortars and is widely used in modern masonry where units and design details are matched to that behavior.

Cement-Lime Mortar

Many widely used masonry mortars include a portion of lime alongside cement. Lime can improve plasticity and water retention, supporting good bond and neat tooling. The balance between strength and permeability shifts with binder proportions and sand selection, so performance is typically specified rather than guessed.

Masonry Cement and Bagged Mortars

Masonry cement mortars are designed for consistent workability and bond in masonry applications, often used in packaged systems for predictable batching. Bagged mortars may also include carefully tuned admixtures for water retention, air entrainment, or color stability.

Polymer-Modified Mortars

Where thin layers and strong adhesion are needed—especially in tile and stone settings—polymer-modified cement mortars are common. Polymers can improve flexibility, adhesion, and water resistance compared with plain cement-sand systems, while still relying on hydration for core hardening.

Special-Purpose Variants

- Colored mortars: pigments for consistent joint tone.

- Rapid-setting mortars: formulated for time-sensitive repairs, with controlled set behavior.

- Repair mortars: engineered shrinkage control and bond performance for patching.

- Water-repellent mortars: additives tuned for reduced absorption while maintaining serviceability.

Performance Characteristics

When engineers and conservators talk about mortar quality, they rarely focus on one number. Mortar must balance strength, bond, permeability, and movement capacity. A joint that is too rigid for a given masonry unit can concentrate stress; a joint that is too weak can erode. The best-performing systems feel balanced for the units, exposure, and detailing.

Related articles: Fortified Stone Castle [Medieval Inventions Series], Cannon [Medieval Inventions Series]

Fresh-State Behavior

- Workability: spreads and beds units cleanly.

- Water retention: supports hydration at the brick/block interface.

- Stickiness and cohesion: helps joints stay full on vertical faces.

Hardened Performance

- Bond: adhesion to masonry units.

- Durability: resistance to weathering and freeze-thaw in suitable exposures.

- Permeability: manages moisture movement through the wall.

- Dimensional stability: shrinkage and microcracking control.

History and Adoption

Mortar itself is ancient, but cement mortar as a Portland-cement-centered material family is tied to the industrial era. A preservation reference from the Kansas Historical Society notes that Portland cement was patented in Great Britain in 1824, imported for a period, and first manufactured in the United States in 1872; it also notes that it was not widely used across the country until the early 20th century.Details

That timeline helps explain why buildings from different periods can contain very different joint materials. In many places, earlier masonry relied heavily on lime-based binders, while later construction adopted more predictable hydraulic binders. As production scaled, cement mortar became a quiet enabler of standardized masonry: regular unit sizes, consistent joint profiles, and repeatable performance in a wide range of climates.

Compatibility in Historic Masonry

In older masonry, the joint is often designed to be a “working” layer—sometimes intentionally softer and more permeable than the masonry units. The National Park Service emphasizes careful material selection and methods for repointing, aiming to preserve the physical integrity of masonry and avoid unintended damage from mismatched repairs.Details In practice, this means mortar choice is about compatibility, not just strength.

Compatibility is multi-dimensional. It includes how the mortar handles moisture movement, how it responds to temperature swings, and how it shares stress with the units. When the joint and the masonry unit “agree” mechanically, the wall tends to age more gracefully. When they do not, repairs can become frequent and finishes can lose their intended appearance. The goal is a joint that stays stable while respecting the wall’s original behavior.

Testing and Specifications

Modern mortar is often specified by performance targets rather than by a single “universal” composition. That approach keeps focus on what actually matters: bond, durability, and moisture behavior in the finished assembly. Laboratory evaluation can consider compressive strength, bond characteristics, water retention, air content, absorption, and dimensional stability—each one a piece of the full picture.

In preservation contexts, testing may extend beyond basic metrics. Color, texture, aggregate character, and tooling response become part of the specification because the mortar is also a visual material. Even small differences in sand grading can shift joint sheen and shadow lines. That is why high-quality work treats mortar as both engineering and craft.

Terminology and Common Misunderstandings

The phrase cement mortar can sound narrow, yet it covers a surprisingly wide range. The same wall might use one mortar for laying units and another for pointing, chosen for finish and exposure. Tile settings might use a polymer-modified mortar that behaves very differently from a standard masonry mortar, even though both rely on hydration.

Another common misunderstanding is treating mortar strength as the sole marker of quality. Strength matters, but so do permeability, movement capacity, and bond. A mortar that is “stronger” on paper is not automatically “better” in a real wall. A well-chosen mortar is one that stays serviceable and supports the masonry units as they age.

Finally, hydration is sometimes mistaken for drying. It is chemistry. Cement-based materials can keep gaining strength while they remain damp, because the binder continues to form hydration products. That basic principle is central to how cement mortar evolves from fresh to firm to long-term stability.

FAQ

Is cement mortar the same as cement?

Cement is the powder binder. Cement mortar is the working material that combines cement with sand and water, shaped for joints and thin layers. The mortar’s behavior depends heavily on sand grading and water retention, not only on the cement.

Why does cement mortar harden if it is not “drying”?

Hardening comes from hydration: chemical reactions between cement and water. A key strength contributor is calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H), which forms as the binder reacts and builds a dense internal network.

Can one cement mortar fit every wall?

No single mortar matches every masonry unit and exposure. A good selection balances bond, durability, and moisture behavior for the assembly. In historic masonry, compatibility with the units and the wall’s original behavior is often the top priority.

When did cement-based mortars become widely used?

Use expanded as industrial production scaled. A preservation reference notes that Portland cement was patented in 1824 and that widespread use in the United States grew later, especially into the early 20th century.

What is the simplest way to distinguish mortar from concrete?

Mortar uses fine sand and is designed for joints and thin layers. Concrete includes coarse aggregate and is designed for bulk structural mass. They may share cement as a binder, yet they are engineered for different placement and performance.